Artist of the 1960s. An innovator of meditative conventionality. Igor Alexandrovich Vulokh (1938–2012) is an important figure in the ranks of artists of the postwar unofficial art. And another striking example of the fact that the talent, like water, sharpens the stone of destiny. Starting conditions are slightly better than none at all. War orphanage childhood, his father died of wounds. It would seem that what can be achieved under such circumstances? But somehow it worked out. At art school he was lucky to meet a teacher — Victor Podgursky, an artist who came back from China in 1947. Next to Vulokh stood a man who had seen the world. Who in the post-war Kazan could talk about Eastern philosophy, about minimalism, about new ideas in foreign painting. Next comes the road to the top. Promising student was promoted to the all-Union level. He was sent to a big exhibition in Moscow, where his landscapes with broad brush strokes and portraits in the Feshin manner impressed the public and influential people. Academics praise. One of the works gets on a postcard (Vulokh later liked to distribute them for a long time). Success. It seems, strike at one point — Feshin landscapes, enthusiastic realism — and then roll on the beaten track.

But no. “Praised”, the teachers grumbled. The Kazan nugget began to disappear in Moscow, skipping classes, studying with who knows who here and there. As a result, the hope of the Republican art is lowered to earth. And the former darling of fortune fails to even get into the coveted Stroganov School. Failure? Catastrophe? Drama? No. A sign of destiny. Everything will happen as it should. The patronage of the Stalinist academician Georgy Nissky helps him get into VGIK. And there new friends: Vasily Shukshin, Igor Voroshilov and Valentin Vorobyov. And here it is, freedom. Tarusian liberty, heady air. And not just the air. With the help of “Paust” — the writer Paustovsky — young troublemakers Vulokh, Eduard Steinberg, Vorobyov and Kamensky set up an exhibition at the local House of Culture. “Unfortunately”, in terms of creativity, everyone was drawn to the “wrong place”. Instead of cows and portraits of rural toilers, abstractions alien to the Soviet people were hung on the walls. They also invited guests from Moscow, which were followed by foreigners. What follows is clear: the scandal, the closure, the firing of the director of the House of Culture and other “consequences”.

This is where the “heroic” episodes of confrontation with the authorities end for Vulokh. His non-conformism becomes purely aesthetic. He no longer participates in any high-profile exhibitions: not in “Bulldozer”, not in “Beekeeping”, not anywhere else. At the age of slightly over thirty, Vulokh becomes a member of the Union of Artists. Regularly participates in official exhibitions at the Kuznetsky Bridge and other halls. He works at the art factory. But in parallel, there is another life. Life of talking about art with Costakis, Zverev, Yakovlev, and close friend Gennady Aygi. There is work for the soul. There is a movement in the comprehension of art. His own distinctive manner, his own way, in which Scandinavian-style austere and oriental laconic landscapes reach a special meditative level.

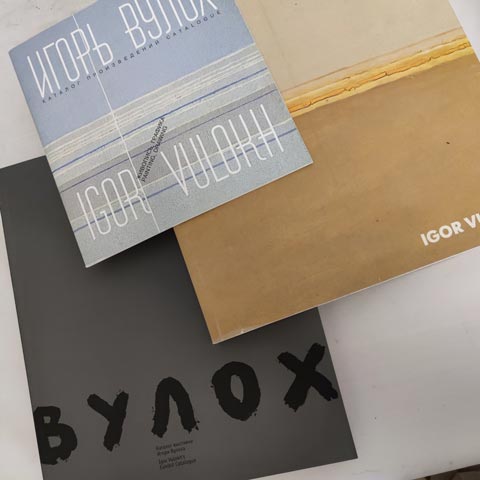

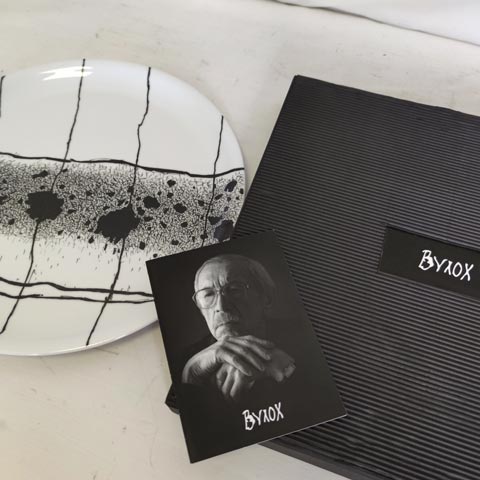

Friends recall that this quiet, kind man used to set himself formal creative goals before starting work — for example, to limit himself to three paints, to go top-down, and to achieve the maximum with limited means. In his later years, he was capable of painting one painting a day. And at the end of his life comes a well-deserved exhibition success. Vulokh is known and appreciated in Germany and Scandinavian countries. Not everyone gets a visit from Tumas Tranströmer, the Nobel Prize winner for literature. He is beginning to be patronized by new Russian and Western gallerists. There is also a surge of interest in Russia. Paintings are purchased by the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum, exhibitions are held at prestigious venues, catalogs are printed. At the very end of his life, the painter and graphic artist Vulokh signs the edition of his first and only porcelain — a series of plates based on illustrations by Tranströmer. He knows that new exhibitions (which were destined to become posthumous) are almost ready ahead. His family — the widow Natalia Tukolkina-Okhota, his stepson Egor Altman — do colossal work. Exhibitions, projects, publications. The family “Vulokh Foundation” helps to deal with authenticity, returns to Russia works “stuck” abroad, is engaged in the popularization of the master's work. And these are all the most important components that form a healthy investment climate.

Now, according to tradition, about money. For now, let's take foreign prices out of brackets, noting only that at the peak of the market 13 years ago, at the prestigious Sotheby's and Christie’s, Vulokh's paintings were selling in the range of $ 10,000–25,000. Then prices adjusted downward, as they did for all the artists of the 1960s, and for Russian classics as well. You can keep them in mind, but more as a historical fact. It is much more important to know what a collector and investor can count on today. And not by complicated ways, but at the competitive open auctions in Russia. And here is what you need to pay attention to in descending order of investment potential.

- Meditative painting of the 1960s–1990s. Vulokh did not like his paintings to be called abstractions, so we use the term “meditative conventionality”. All the more so because his minimalist paintings often had a figurative basis and quite genre-specific titles: “winter”, “autumn landscape”, “still life”, etc. He even had “nude”, though very specific. Today, such paintings of classes 50 × 70 or 60 × 80 can be found at auctions in the range of $ 3 000–6 000. (225,000–450,000 rubles). Those for three — strong, but simpler. And for six — actually a museum level. If you can “catch” cool stuff for this money, it can be considered a good investment.

- Paintings and graphics on paper, class 60 × 80. Depending on the plot and the degree of creative luck, such works can cost in the region of 150,000–200,000 rubles. That is, approximately $ 2,000–3,000. Among them, there are particularly spectacular things, but the investment potential (the possible rate of price growth) for graphics is generally lower than that of painting.

- Porcelain — plates. The choice is limited here. There is only one series with drawings to Tumas Tranströmer. The plates are painted, as they usually are, by another artist according to an agreed sketch and are provided with a signed Vulokh certificate. They are priced differently in different places. But today there is still a chance to buy individual plates on the open market for the equivalent of $ 1,000. That's a good option. I have almost no doubt that they will go up in price as well.

The basic advice for investing in Vulokh fits into the standard logic for effective investments in the 1960s artists. The most prudent strategy is to accumulate a budget and wait for the opportunity to buy the best available on the market. Ideally, it's better to set aside the $ 6,000 or slightly more you're looking for to buy a solid piece from a museum-level painting. And such chances now really fall 5–10 times a year. You need to bide your time, to seize the moment. And remember that with the growth of the economy (even if “crooked” and disproportionate) prices for paintings by an artist of this level, as Vulokh, and with such driving forces, are simply obliged to grow.

Vladimir Bogdanov, specialist of the auction of Russian art ArtSale.info

Watch also a video review on investing in the works of Igor Vulokh on our YouTube channel:

- Log in to post comments