It's supposed to be good all at once. The artist is first rate. The works are still available on the market. Prices — for any wallet: from 30,000 to 800,000 rubles. The paintings are recognizable, spectacular, interior, not only eye-catching, but drawing attention to themselves. Seemingly ideal conditions for the start of the collection. But nevertheless with Sveshnikov collecting usually does not start.

Why not? The works of this author require from the future owner not only immersion in the subject, but also a certain collector's courage. The inhabitants of Sveshnikov's worlds are phantasmagoric characters, devils, fallen angels, skin-covered skulls with narrow lips (actually Sveshnikov's self-portraits), and even the death-friend keeping an eye on everyone. Is it conceivable to hang such a “horror” at home?

Over time, skepticism wears off. And at first — yes: even if novice collectors buy (after all, the name!), they try to choose softer plots. First of all they look for things that are commercial — without dead bodies, without grave fences, and with less devils. Almost twenty years ago I chose the same way. Now I regret very much. I wish I had been braver then. After all, today it is clear that choosing Sveshnikov by the criterion “softer” is like looking for “calmer” in Rembrandt, “more positive” in Goya or something “more erotic” in Lucien Freud.

On the other hand, why reproach yourself? Apparently, the understanding of Boris Sveshnikov's work comes through five phases of crisis perception: denial — anger — bargaining — depression — acceptance. And this journey from denial to acceptance can easily take those twenty years.

What is important to understand about Sveshnikov's “devilry”? The phantasmagoric, infernal and “afterlife” in the artist's plots is not some artificial method of recognition, not some kind of found “trick”. This philosophical and artistic interpretation of an endlessly traumatic life experience is a memory of the bottomless horror that he had to endure in his youth.

In 1946 the 19-year-old romantic, yesterday's teenager was arrested on a denunciation, imprisoned and then sent to the camps. The accusation against Sveshnikov and his friend Lev Kropivnitsky included fabricated nonsense about participating in a terrorist organization to assassinate Stalin. And if there was even an ounce of truth in it, he was sure to be shot. But as it was, he “got off lightly”. Ten years in a camp. “Luckily”.

Hunger, cold, logging, excavation. After a few months in the camps of the Ukhtizhemlag system, Sveshnikov was exhausted by illness and actually came to the threshold of death. His letters home (published by “Memorial” in the book “Boris Sveshnikov: Camp Drawings”) are definitely not for the faint of heart. This is not even “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”. It just makes your hair stand on end and your heart break. For a long time the poor fellow could not understand for what sins he was doomed to such torment. From overwork, hunger and disease, the young Moscow artist turned into a goner who was on the verge of losing his mind. The support of his parents and the help of kind people helped him to survive. Repressed geologist Nikolai Tikhonovich (according to other information, paramedic-convict Arkady Steinberg) helped to attach the asthmatic man, who was no longer fit for “general work”, as a watchman. Father and mother helped as much as they could and sent paints and brushes. And the freed Ludwig Seja — the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Latvia — helped to transport a significant part of the camp drawings to freedom. Thanks to him, as well as to Arkady Steinberg, those drawings have survived to this day.

Sveshnikov was released in 1954. With eight years behind him, he headed for Tarusa. There, beyond the 101st kilometer, lived his old friend, the same camp paramedic, himself a former prisoner, Arkady Akimovich Steinberg. In his hospitable village home, Sveshnikov recuperated, painted, and studied with Akimych's son, Edik, the future famous nonconformist Eduard Steinberg. Then things began to get better. Paust (the same writer Konstantin Paustovsky), who lived in Tarusa, helped Sveshnikov get a job at the “Khudozhestvennaya Literatura” publishing house. This allowed the artist to earn his living almost to the end of his days as a book illustrator. By the way, you probably had to hold his books in your hands. For example, I remember his illustrations of Andersen's fairy tales. In 1957, after his rehabilitation, Sveshnikov returned to Moscow. With time an opportunity to participate in group exhibitions appeared (he did not have lifetime personal exhibitions). And gradually, somehow, everything more or less settled down.

Why mention camp biographical details? Because the hardships he endured in the 1950s provide a key to understanding Sveshnikov's particular imagery in the 1970s and early 1990s. In one of his letters to the publisher, Sergei Dovlatov wrote: “According to Solzhenitsyn, the camp is hell. But I think hell is ourselves”. I think Sveshnikov would have reconciled the two writers. He would have proved to them that both are right in their own way.

Sveshnikov's works are a special form of the Vanitas genre — an allegorical reminder of the vanity and transience of life. And, of course, a reminder of the inevitability of death. Five hundred years ago the Flemish reverends edifyingly built the symbolic still lifes around the skull. But Sveshnikov went further. He proposed a radical ideological solution. In place of the Baroque Vanitas he proposed the barrack Vanitas. Why frighten us with inevitability? There is no future with inevitable punishment for sins. Anything the future could frighten us with is already perfectly coexisting with humanity. And death-mate and her companions are not some sinister otherworldly characters, but entities that have long dwelt nearby. Not everyone notices them. But for those who have been on the other side, it is no secret.

How he came to this idea is anyone's guess. A decisive withdrawal of the theme of death and Inferno from the sphere of the sacred could be for Sveshnikov a way to overcome trauma and a form of psychological therapy. Something similar to oriental bushido, which suggests a samurai to act as if he were already dead, to suppress the paralyzing fear of death and keep his composure. Only by getting rid of the fear of death can one live a full life, they say. However, again, this is just an assumption, a guess. Sveshnikov did not manage to get rid of the terrible memory to the end. Those who knew him remember that the camp forever left a mark of suspiciousness on him: “curtain the windows”, “keep your voice down”. Toward the end of his life, he became more and more withdrawn. And how could it be otherwise? Sveshnikov died in 1998 in a Moscow hospital from a severe attack of asthma. He is buried at the Vagankovskoye cemetery.

Now about the legacy and the market situation.

I should warn you right away that Sveshnikov's camp drawings and romantic paintings of the 1950s are unlikely to be available for purchase today. All of these have long since settled in important private collections. At Russian public auctions, such works practically do not happen. In other words, it is such a rarity that it makes no sense to consider it in an investment plan. But, fortunately, there is enough other collectible material — there is plenty to choose from.

What to pay attention to in the first place? I'll list in descending order of investment attractiveness:

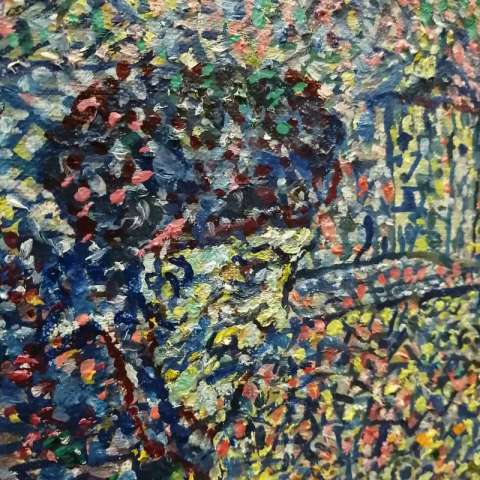

- “Divisionist” paintings of the 1980s — early 1990s. Usually these are paintings in a dominant blue palette, which from afar look as if painted with dots. A painting of this size, roughly 70 × 50, today costs in the range of 500,000–700,000 rubles. Smaller paintings start at 400,000. The word “divisionism” in Sveshnikov's case is not put in quotation marks for nothing. It is a convention. After all, his paintings are not even painted with dots. Rather it is a web formed by complexly colored triangles and polygons. And in some works, if you look closely, these are not dots at all, but hundreds of small skulls. There is an opinion that in Sveshnikov's “divisionist” works we should distinguish two degrees of elaboration — more detailed and less detailed. More detailed, they say, is better and should therefore cost more. I do not agree with this. There are no clear rules. More than once I've seen examples where a “less detailed” painting was superior in its artistic merits to “more detailed” ones. So you have to evaluate the level of the painting as a whole. And the dependence of price on the depth of technical elaboration should not be considered a dogma. Yes, sometimes there is a correlation. But not necessarily, and not always a direct correlation.

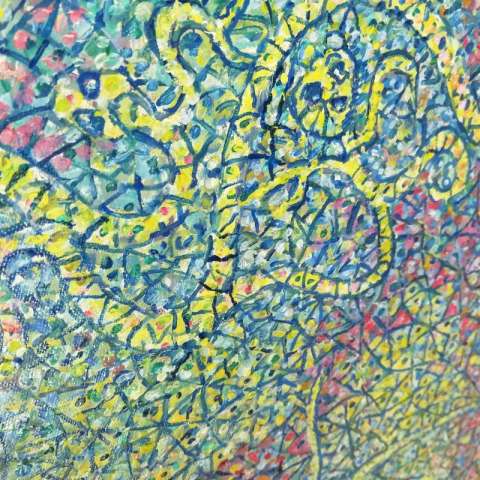

- “Divisionist” color drawings. Usually these are small graphics of about 25 × 30, done in ink and water-soluble paint. Today you can buy it in the range of 70,000–100,000 rubles. What is good about color graphics? It is essentially painting in miniature. With all of Sveshnikov's trademark specific imagery, with otherworldly characters and phantasmagorias. Often the author's title is written on the back — it makes your blood run cold. “Cemetery Visit”, “Dead Angel” — these are still what they call soft versions.

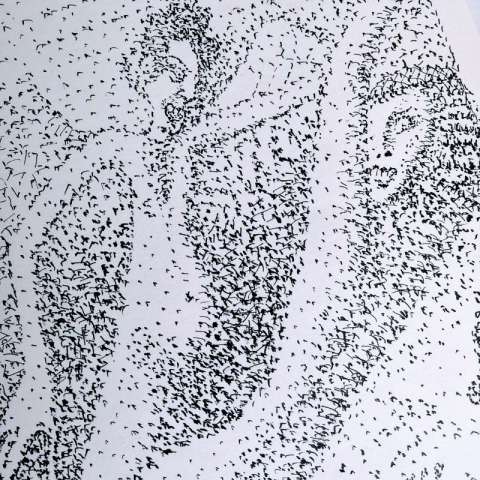

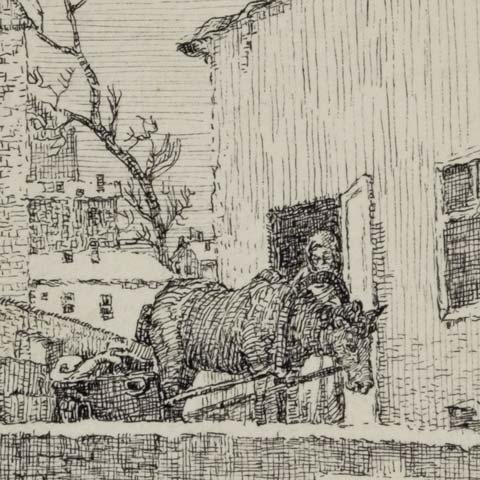

- “Divisionalist” black-and-white drawings. The essence is the same as the color ones. Only they are often larger — 30 × 40 or so. And black-and-white drawings cost about half as much as the color ones — from 30,000 rubles. Not least due to such high availability, black-and-white graphics are very liquid, that is rarely unsold.

- Romantic watercolor landscapes. Sveshnikov's watercolors on large Whatman paper 50 × 70, signed, generally pleasing to the eye, can often be found at auctions. Unmistakably recognizable birch trees, houses, without any devilry and infernality. You could hang them in a nursery. And they are not expensive — about 35,000 rubles. Nevertheless, they do not go off like hotcakes. And quite often remain unsold. Why? Perhaps because they do not have Sveshnikov's nerve, his gloomy Kafkaesque energy. To hang them for beauty is all right. But I cannot recommend them for investments.

- Book Illustration. It is known that for Sveshnikov working on books was not a chore. He sincerely loved illustration, immersed himself in the atmosphere of the work and passionately worked on the design of the literary basis. Not surprisingly, that from under his pen came out inspired, precise drawings, in an unmistakable author's style. Sveshnikov devoted more than thirty years to book graphics. There are quite a lot of drawings left. And they are not uncommon on the market. Small sizes cost from 20,000 rubles, and sometimes even cheaper. Nevertheless. In general, it is the same story with them as with romantic landscapes: a good option for beauty, but poorly suited for investment.

What will happen next with the prices for Sveshnikov? He is still being bought very well. Even in 2020, the coronavirus year, almost everything that was put up for auction was sold. And in the future interest in his work will only grow.

Why do I think so?

First of all, it is striking how quickly the demand for strong emotions is growing in our society. If the Soviet audience fainted from the film adaptations of Gogol, then the current generation 45+ is difficult to get through even by Stephen King. We need more and more acute intellectual sensations. And Sveshnikov provides them. As for “devilry”, the area of the unknown has not frightened many for a long time. It is safe to say that more and more collectors are ready for Sveshnikov's complex “optics” every day. Especially new, young collectors.

Secondly, Sveshnikov's works are characterized by a paradox that many experienced collectors have noted. For all the specificity of the “deceased” themes, his paintings do not look gloomy. They do not create a crushing impression. A special palette, this radiating light turns them into completely interior works, which you can live with. This is exactly the case when you involuntarily come to the pretentious conclusion “beauty conquers death”. So Sveshnikov's time is really coming only now. Before our eyes, there will be a revision of the significance of his work for the history of post-war art. And this process can be accompanied by a significant increase in demand and prices.

What should compilers of investment collections consider in this regard? The best examples of painting have the greatest potential for price growth. Therefore, in a priority order, buy oil paintings by Sveshnikov. In other words, try to allocate as much as your budget allows for the best pictures. The meaning is this: if you have 600,000 rubles, it is better to buy one painting for 600,000 rubles than 20 drawings for 30,000 rubles. And the logic is the same with graphics. If you have 100,000 rubles, then it is better to buy one color “divisionist” drawing for 70,000 than three black-and-white drawings for 30,000 each. There are nuances. But in general the recommended approach to compiling an investment collection remains unchanged: don't spread yourself thin, choose the most expensive and highest quality, don't chase quantity, take quality.

Vladimir Bogdanov, art market specialist, ArtSale.info auction

Watch a video review of investing in the works of Boris Sveshnikov on our YouTube channel:

- Log in to post comments