1960s UNOFFICIAL ART

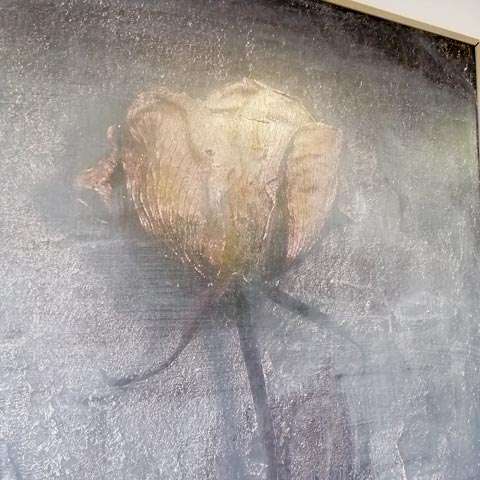

KUPER Yuri Leonidovich (1940) Rose. Sfumato. Foam cardboard, author's technique. 195 × 135

The inventor of the sfumato technique is considered to be the great Leonardo da Vinci. He figured out how to give an image a subtle blur, and learned how to reach a state “on the edge” — when the texture just begins to dissolve in the air and a haze appears. It is this technique that partly explains the mystery of Mona Lisa's smile.

Sfumato sets the mood for many of the works of the 1960s artist Yuri Kuper. Even the word itself is associated with his name today. And the very old technique in his hands has received a new development. Kuper's works, at different angles and under different lighting, are amazingly transformed beyond recognition. And, importantly, it is the lack of light that benefits them — new depths appear and, can you believe it, new colors. In particular, our rose lights up when viewed from an angle. But the shade suits it best.

Yuri Kuper is a renaissance artist, a man talented in everything. He writes poems, draws pictures, makes artist's books, develops theatrical interiors and scenery, and creates architectural projects. In particular, he developed a project for a new Sretensky monastery, a project for a synagogue in Perm and a curtain design for Gergiev's Mariinsky Theater. Kuper emigrated from the USSR in 1972, and for almost thirty years he has worked in exile: in France and the USA. Now he works in Russia.

ZVEREV Anatoly Timofeevich (1931–1986) Self-portrait in a hat and a plaid coat. 1950s Watercolor, whitewash, oil on paper. 57.6 × 42.2

A unique early work by Zverev in the 1950s. Written in a Tashist manner, the self-portrait belongs to Zverev's valuable analytical and philosophical cycle of portraits. According to expert Valery Silaev, the work is of museum importance.

NEMUKHIN Vladimir Nikolaevich (1925–2016) Land and Will. Dedicated to K. Malevich. 1995. Acrylic on canvas, mixed technique. Tondo. Diameter 48 cm

A rare plot — a suprematist black rectangle and characters from Malevich's peasant cycle in a conceptual arrangement by the 1960s artist Vladimir Nemukhin. A piece with meanings! And the primary source of these meanings is Malevich himself. The characters in his second peasant cycle are strange toilers, symbolically deprived of faces and hands. And their clothes are loaded to the point of sketchiness. In contrast to the first romantic peasant cycle, which was almost pastoral, the second cycle is a cycle of disappointment. In fact, it is even a cycle of protest. Malevich states that there is no peasant freedom, no “liberation of laziness” for creativity, on the contrary, there is enslavement again. The ideas of revolution in fact turned out to be utopia. The good intentions of an enthusiastic Herzen's Populism were trampled into dust. And in the 1930s, this was already quite obvious.

Nemukhin called this painting “Land and Will” — the name of the populist organization, on the splinters of which the terrorist “People's Will” was later formed. But from the beginning the idea was well-meaning: urban romantics tried to convey the ideas of freedom to the dark peasant village. The “walks to the people” began. Educated people set out to tell the peasants about freedom of religion, about a progressive way of life, about self-government. They thought that the disenfranchised peasants would open their eyes. And those in response only: “What do you please, sir?” Words failed to convince, hopes for a peasant revolt dried up. And the hotheads turned to terror. They killed odious officials and policemen. In 1887, Alexander Ulyanov, a 21-year-old member of the “People's Will” party, was hanged by the tsarist authorities for plotting an assassination attempt on Alexander III. And the authorities weren't too worried about it: “Everything is done according to the law!” And 31 years later, Ulyanov's brother cruelly avenged his brother: he created the conditions for the destruction of the royal family and put an end to the tradition of succession to the throne.

Such is the dedication to Malevich. Such is the cycle of meanings. Vladimir Nemukhin. 1995. In the examination of Valery Silaev, museum significance was noted.

STEINBERG Eduard Arkadevich (1937–2012) Composition with black triangles. 2002. Paper, gouache, applique. 48 × 63 (in light)

Another dialogue with Malevich from a representative of the second Russian avant-garde, Eduard Steinberg. Among his teachers was Boris Sveshnikov, a friend of his father's who had recently been released from Stalin's camps and who lived in their house in Tarusa. Later, the underground artist Steinberg became close to the “Sretensky Boulevard Group”, which included Kabakov, Bulatov, Sooster, and Yankilevsky. Steinberg participated in many high-profile exhibitions of unofficial art: the Druzhba House in 1967 and the Beekeeping Pavilion at VDNKh in 1975. After perestroika, Steinberg emigrated. Since the late 1980s he lived in France, working with the Claude Bernard Gallery. The last years he lived in two cities: in winter in Paris and in summer in his beloved Tarusa. Now a museum is organized in Tarusa — the workshop of Eduard Steinberg under the auspices of the Pushkin Museum.

VULOKH Igor Alexandrovich (1938–2013) Landscape with yellow. Late 1960s — early 1970s. Paper on cardboard, oil. 44 × 59.5

An outstanding 1960s artist, with a recognizable style, a master of metaphysical abstraction. Back in 1961 (before Manezh-62 and other high-profile exhibitions), Vulokh, Steinberg, Kanevsky and Vorobyov held an exhibition of free art in the House of Art in Tarusa. And provoked the first international scandal. The artists, out of the goodness of their hearts, invited foreigners to the exhibition. And they just came. Diplomats, journalists. But they weren't supposed to. The exhibition was immediately shut down. A lot of noise. The director was fired. And Vulokh and Vorobyov were expelled from VGIK for unsuitability. For approximately such kind of abstract landscapes. This one was just painted in the 1960s.

LEONOV Pavel Petrovich (1920–2011) Dances to the harmonica in the village. Oil on canvas. 116 × 83.5

Meter sized Leonov is one of the most beautiful we've seen. Romance. Dancing to the harmonica in the village. Well, what else to do. Pavel Leonov is one of the main representatives of Russian naive art. He began to draw at the end of a difficult and hard life. He was a laborer, began to learn painting in a correspondence institute, where he was taught by Mikhail Roginsky. And here at the end of the 1990s, the artist Leonov was born — with his fabulous world, where there is no suffering, everyone is happy, and life is reasonable. Utopia with dancing to the harmonica. Leonov. Meter size.

BELENOK Petr Ivanovich (1938–1991) The Leap (Guarding their own). 1990. Paper, ink, mixed technique. 86 × 61

The rubric closes with a very recognizable, characteristic, charged graphic of the non-conformist Petr Belenok. “The Leap” (another title is “Guarding their own”) is a vivid example of “panic realism”. The large-format work will become a jewel in the collection.

RUSSIAN ABROAD

BURLIUK David Davidovich (1882–1967) Girls at the Fence. 1959. Oil on canvas. 20.5 × 25.3

Expert Irina Gerashchenko notes that the plot of the painting “Girls at the Fence” could have been inspired by Burliuk's trip to the USSR in 1956 or to Czechoslovakia in 1957. Slavic types. There is a mill in the background. A moody thing, pleasant, everything is good in it. And it is precisely this kind of Burliuk, “dense”, with a Russian theme, that is most appreciated by collectors. I should add that the painting is compact and will easily find a place even in a large, established collection.

YAKOVLEV Alexander Evgenievich (1887–1938) Two nude figures. 1920s. Charcoal, sanguine on paper. 61 × 43. 60 × 40 (in light)

Alexander Yakovlev was a member of the “World of Art” association. The revolution caught him on a creative expedition to the Asian continent. The artist decided not to return to Russia. Today, Alexander Yakovlev, as well as his friends in the “Russian Paris” Vasily Shukhaev and Boris Grigoriev, is among the most expensive Russian artists. His auction record is 5.5 million dollars. This large sanguine by Alexander Yakovlev has an assessment of “museum value” indicated in the examination.

- Log in to post comments